Essay

For many US college students, the transition from high school narrative writing to rigorous academic persuasion can feel like a daunting leap. Whether you are navigating a Freshman Composition course at NYU or tackling a political science thesis at UCLA, the ability to construct a compelling argument is the hallmark of academic success.

A persuasive essay isn’t just about having a strong opinion; it’s about architecting a logical journey that leads your reader to a specific conclusion. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), only about 27% of high school seniors perform at or above the “proficient” level in writing. In the competitive landscape of US higher education, mastering the structure of persuasion is what separates an ‘A’ grade from a ‘C.’

The Anatomy of a Winning Persuasive Essay

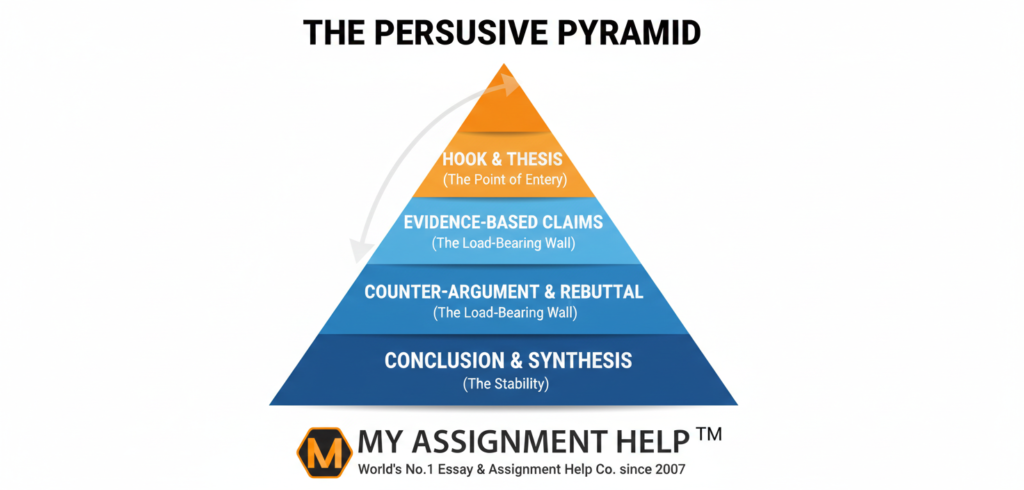

To influence a scholarly audience, your essay must follow a rigid yet fluid structural framework. This ensures that your ideas are not just heard, but are intellectually unassailable.

1. The Introduction: Hook, Context, and Thesis

Your opening paragraph is your first—and often only—chance to capture the reader’s attention. It should start with a compelling “hook.” This could be a startling statistic, a provocative question, or a relevant anecdote. For students struggling to find that perfect opening line, exploring a variety of essay hook examples can provide the creative spark needed to engage a cynical professor.

Following the hook, provide necessary background information to situtate your topic within current academic debates. The introduction culminates in the thesis statement. In US academia, the thesis is typically a single, concise sentence that outlines your central claim and the roadmap of your supporting points.

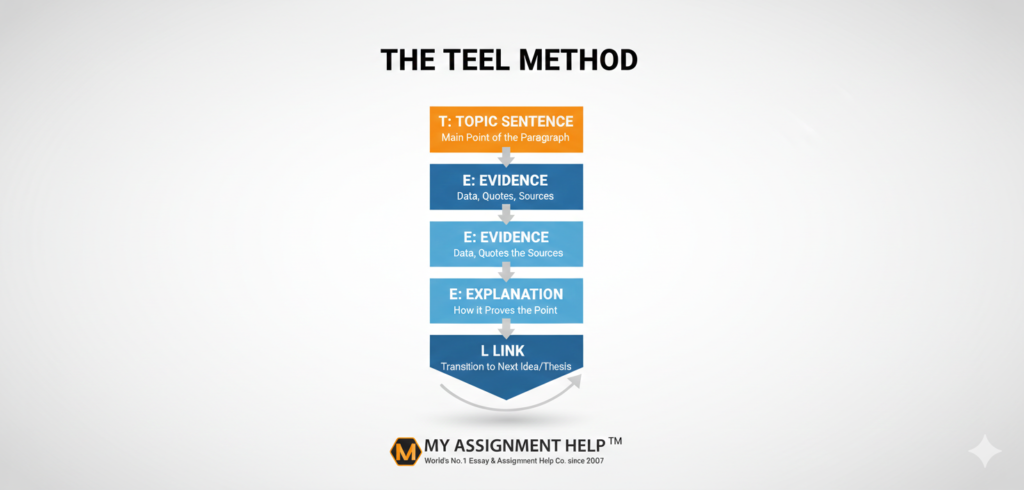

2. The Body Paragraphs: The “TEEL” Method

If you find yourself overwhelmed by the demands of collegiate research, seeking essay writer service can be a strategic way to understand how to synthesize complex data into a coherent structure. A well-structured body paragraph generally follows the TEEL acronym:

- Topic Sentence: Clearly state the main point of the paragraph.

- Evidence: Back your claim with data, scholarly quotes, or primary sources.

- Explanation: Explain how the evidence proves your point.

- Link: Transition smoothly to the next point or back to your thesis.

3. Addressing the Counter-Argument

A unique requirement of US college-level writing is the “Refutation” or “Concession” section. To demonstrate high-level critical thinking, you must acknowledge the opposing view. By identifying the strongest argument against your position and then systematically dismantling it with superior evidence, you strengthen your own credibility (Ethos).

4. The Conclusion: Beyond Redundancy

Do not simply repeat your introduction. A sophisticated conclusion synthesizes your findings, restates the thesis in a new light, and discusses the broader implications of your argument. End with a “Call to Action” or a “Final Thought” that leaves the reader reflecting on the significance of your topic.

Data-Driven Insights: Why Structure Matters

Research from the Journal of Writing Research indicates that students who utilize a formal outlining process score 15-20% higher on argumentative clarity than those who “free-write.” Furthermore, a survey of US college faculty revealed that “logical flow and structure” were ranked as more important than “originality of idea” when grading undergraduate work.

Recommended Resources for US Students:

- Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL): The gold standard for MLA/APA formatting.

- The Chronicle of Higher Education: Excellent for sourcing contemporary debates.

- Statista: For high-quality, data-driven evidence to bolster your arguments.

Key Takeaways

- The Thesis is King: Never start writing without a clear, debatable claim.

- Quality over Quantity: One well-evidenced paragraph beats three vague ones.

- Acknowledge the Opposition: Showing you understand the other side increases your “Ethos.”

- Transition Verbally: Use words like “Furthermore,” “Conversely,” and “Consequently” to guide the reader.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How long should my thesis statement be?

A: Ideally, one sentence. It should be a “road map” for your entire paper, located at the end of your introductory paragraph.

Q: Can I use “I” in a persuasive essay?

A: In most US colleges, third-person objective (e.g., “The evidence suggests…”) is preferred over first-person (e.g., “I think…”). However, always check your specific professor’s rubric.

Q: How many sources do I need?

A: A standard 1,000-word college essay typically requires 3 to 5 peer-reviewed sources to meet the standards of academic rigor.

Q: What is the difference between an argumentative and a persuasive essay?

A: While similar, an argumentative essay relies strictly on logic and data, whereas a persuasive essay may also appeal to the reader’s emotions (Pathos).

About the Author: Dr. Sarah Jenkins

Dr. Sarah Jenkins is a Senior Academic Consultant at MyAssignmentHelp. With over 12 years of experience in Rhetoric and Composition, she has helped thousands of students across the US navigate the complexities of academic writing. She previously served as an adjunct professor at a leading Ivy League institution and specializes in helping international students adapt to US grading rubrics. When she isn’t auditing academic content, Sarah enjoys hiking in the Pacific Northwest and volunteering at local literacy centers.

References

- National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). (2023). Writing Assessment Results.

- Purdue University. (2024). Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. Purdue Online Writing Lab.

- Journal of Writing Research. (2022). The Impact of Structural Outlining on Undergraduate Performance.